Why George Tapan, at 74, remains king of showing the world the beauty of the Philippines

If there’s one photographer known to really “Love The Philippines,” it’s George Tapan. For five decades now, he has been helping promote the country through his photographs that appear in DOT campaigns, travel marts, and airport terminals.

He brought honor to his homeland by winning two Pacific Asia Tourism Association (PATA) Gold awards, an ASEAN Tourism Association award, and a 2011 National Geographic Photography competition. The man has published over ten books on Philippine tourism and culture. At 74, he still churns out some of the most magnificent images spotlighting different parts of the Philippines. And that’s why he’s still considered the country’s master travel photographer.

Days before this interview, the Department of Tourism shared a photo of Mayon Volcano posted by Tapan on Nikon Philippines’ Facebook group. It showed a couple lounging under a white beach umbrella at the foothills of the volcano famous for being shaped like a perfect cone. He shot it for Misibis Bay to evoke the luxury escape the resort promises. To nail the shot, he had to ride a helicopter.

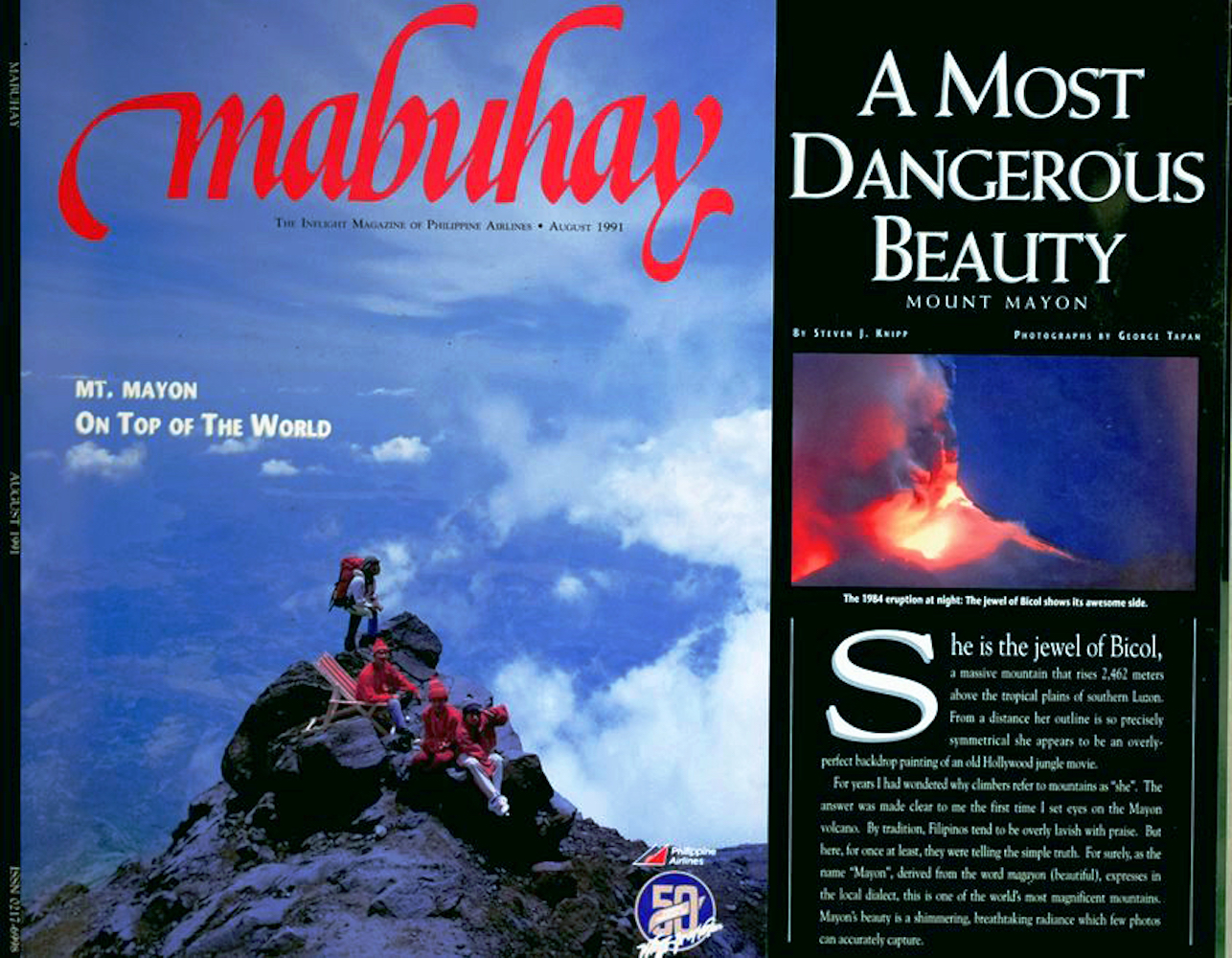

We later discover while browsing the said Facebook group that the acclaimed photographer has quite an arsenal of iconic Mayon photographs. One of the most breathtaking was shot for a cover of Mabuhay magazine back in 1991. Photographed from the top of Mayon, it shows four mountaineers gathered on a pile of boulders seemingly ready for a picnic, taking in the majestic view of clouds and the Albay landscape below—which also serves as the backdrop for the spectacular image.

To achieve the composition, Tapan left nothing unplanned—from the blocking of his cast, to the clothes they wore, down to the props. “Hinanap ko ang oldest mountain guide sa lugar na yun. Itinanong ko kung pwede niyang isama ang dalawang apo niya ages 11 and 9,” Tapan recalls. It was the lensman’s first time to climb the volcano, same with the writer Steven Knipp. About 20 volunteers helped make the shot possible.

Tapan shows us another image of Mayon with a butanding swimming in the foreground. “Nabalitaan ko na may sightings ng dalawa o tatlong butanding sa Legazpi, Albay, so pinuntahan ko agad,” the photographer says.

He didn’t want to disturb the whale sharks before he could accomplish his agenda, so Tapan opted to use a kayak instead of a motorized banca. The butandings did make an appearance during his sail. “Kung makikita mo ang disenyo ng P100 bill na may butanding sa foreground at Mayon Volcano sa background,” Tapan says, “ganoon ang pagkakakuha ko.”

But something happened after taking that incredible shot. “Yung butanding lumapit sa ilalim ng aking kayak. Paglingon ko, na-outbalance ako, tumaob yung kayak ko. Buti na lang naka-life vest ako,” the lensman tells ANCX, recalling his panic. “Naitaas ko ang camera ko pero nabasa rin.”

He was able to save the SD card containing the photographs, but not his camera. “Pero kahit na nasira ang camera ko na worth P100,000 nakuha ko naman ang shot na gusto ko,” he smiles as he relives the moment in his mind.

Tapan, who was born and raised in Unisan, Quezon, was the eldest among eight children. His father Gregorio was a photographer in their small town.

“He took portraits, ID pictures, covered weddings and different events, occasions. Lahat ng services na pwede i-offer ng isang photography studio,” the son says. Since photography was the family’s bread and butter, the young George learned the craft early on, and so did brothers Donald and Edgar. George never made it to college. The boy from Quezon went straight to work.

In the late 1960s, the teenage George made a jueteng bet and luckily won. From his prize money, he bought his very first camera, a Yashica box type. “Para siyang Rolleiflex,” Tapan recalls. “So masaya na ako nun kasi hindi na ako nanghihiram at hindi ko na itinatakas ang camera ng father ko.”

George had big dreams for his career in photography. Seeing copies of National Geographic and Life magazines in book stores, he knew the images on those pages were the kind of photographs he wanted to take. “Gusto ko yung may buhay, may story, may soul ang bawat picture, mapa-personality man yan, food o destination.”

In 1970, he embarked on his first big career adventure by moving to Manila. He knew he had to build connections first in the publication industry, and that this would be extra challenging since he didn’t have a degree in Fine Arts. A Fine Arts degree was a typical requirement for photographers who wanted to go pro in those days.

George was determined to make photography work for him. He first offered his services as a still man in the movies and luckily got gigs in film productions that starred the kings of Philippine movies: Joseph Estrada, Fernando Poe Jr., and Dolphy. This became his ticket to meeting the lifestyle writers and becoming a freelance photographer who shot for publications like The Manila Times’ Saturday Mirror magazine, and Fina, a fashion magazine.

In 1974, he applied as a staff photographer for Sunburst, a lifestyle and travel publication. “In-interview ako ni Max Soliven [who was managing it],” Tapan recalls. There, he experienced shooting everything from food to destinations, including famous personalities. “I took photos of Nora Aunor and Hilda Koronel. I was sent to Jakarta and Tokyo. So natupad na ang gusto ko na mag-take ng mga shots na gaya ng sa Life magazine!”

In 1980, he started to dip his toes in advertising photography, eventually setting up his own office, Third Eye Visual, at Century Park Sheraton Hotel. In 1987, when Soliven started publishing Mabuhay, the Philippine Airlines’ inflight magazine, Tapan was hired to become its director of photography. It was trip after trip after trip. “I go to places kung saan lumilipad ang Philippine Airlines,” he says.

One of the highlights of Tapan’s career as a travel photographer was winning the National Geographic photography contest in 2011.

At that time, he was working on a coffee table book on Palawan entitled “Into the Green Zone, Palawan Islands” and was thinking of an impactful photograph to close it. He thought it should show a rainbow, a symbol of hope, optimism, the promise of good things to come. But when will a rainbow appear?

Then as he and his crew were on their way home from Onok Island, there was a downpour. They decided to stop sailing for a bit and wait for the skies to clear up. Tapan told his guys they could take a dip in the ocean if they wanted. As his crew members frolicked in the water, an amazing sight appeared on the horizon.

“Biglang nabutas ang clouds at yung rays ng sun lumabas,” remembers Tapan. And then his desired rainbow showed up. “I told my staff, ‘Do not move. Just follow my orders. Ako na ang bahala.’”

When the group returned to Manila, Tapan browsed through his shots. He found out the National Geographic was having a worldwide photography contest called “Captured Moment.” He immediately thought of two photographs with rainbows he could submit. One was a photo of Onok Island, and the other was a photo of France after a rainstorm. The end of the rainbow in the France photo rested on the chapel of Saint-Florentin at the Château d’Amboise, a manor house in France’s Loire Valley, where Leonardo da Vinci was originally buried.

“Sabi ko, kung manalo ang Pilipinas, makakatulong ako sa Pilipinas. Kung mananalo ang France, I will get the award but the credit goes to France,” Tapan recalls. So he chose to submit his photograph of Onok Island on the day of the deadline.

After five days, Tapan received an email from NatGeo congratulating him on being one of the winners of the “Captured Moment” contest. He was later informed he won in the Places category, which received 21,000 entries from 120 countries around the world. According to judge Tim Laman, Tapan’s photo “showed a perfect sense of timing and composition in the way he captured the two small human subjects in this beautiful scene, and that really made the shot.”

We ask the veteran lensman what qualifies as a George Tapan signature shot—or what’s “Georgegraphic,” as he likes to call it. He says it would contain elements the viewer would be able to connect to a particular place or culture.

“Noong gumawa ako ng campaign for Camiguin Island, nag-shoot ako sa sandbar. Pero nagdala ako ng isang magandang Pilipina na nakausot ng sarong at may sunong na lanzones,” he tells us. “Dahil sa lanzones, kahit walang caption, maiisip mong ito marahil ay kuha sa Camiguin.”

Similarly, when he photographed the whale sharks in Legazpi, Albay, he made sure the Mayon Volcano was in the background.

A Georgegraphic photograph would have elements—people, food, or textile—that would make the image difficult, even impossible, to duplicate. This, says the old man, entails planning. “Nung kinunan ko ang mga Tiboli, yung sinuot nilang damit, yung gitara, binili ko yun. Nasa bahay ko ang mga yun. So kahit sinuman magpunta doon, they will not be able to produce the same shot,” Tapan says with pride.

The travel photographer says this effort to make his images unique and hardworking applies when it came to choosing photographs for the DOT’s “Love the Philippines” campaign. “The tagline has to come with a strong image that would connect it to the Philippines. Hindi basta waterfalls or any landscape in the country.”

Through photography, Tapan was able to provide for his family through the years. His three children, Harold, Hannah, and Harvey, are also established photographers and now have families of their own. The Tapan patriarch was not only able to secure real estate properties for the family, he was able to amass a collection of over 50 cameras. He is a doting lolo to six cute apos. “Kung nai-set up mo na ang kinabukasan ng iyong pamilya, for me that is already part of your success,” he says.

Does Tapan have any remaining goals to pursue? He’d like to publish a book chronicling his 50 years as a tourism/travel photographer. “Lahat ng iconic na litrato na ginamit to promote Philippine tourism will be included there,” he says. He is also planning to build a photography museum in Binangonan, Rizal, so photography enthusiasts have a place to go if they want to learn and or just enjoy the craft.

What Tapan believes to be the reason he remains relevant as a travel photographer is because he travels on his own. In fact, after this interview, he is once again headed to Legazpi, Albay, this time to photograph the recent activities of the Mayon. “Marami kasing nag-aabang ngayon ng mga nangyayari sa Mayon. May nakikita akong nagpo-post ng photos, hindi na realistic ang itsura,” he says. While talking about the preposterous volcano images he’s been seeing online, he in the process reveals what makes up his standard for a good photograph. “The shot must be realistic and informative, kasi as photographers, we are recording history as it unfolds. Hindi dapat ine-edit.”

Through his vast experience, Tapan has become a master in capturing an image that could stand out alongside images of similar or other destinations. “Dapat naipapakita natin ang iba’t ibang aspeto ng ating kultura, gaya ng mga tao, pagkain, makukulay na textile,” he says. “Yun ang formula ng mga litrato ko.”